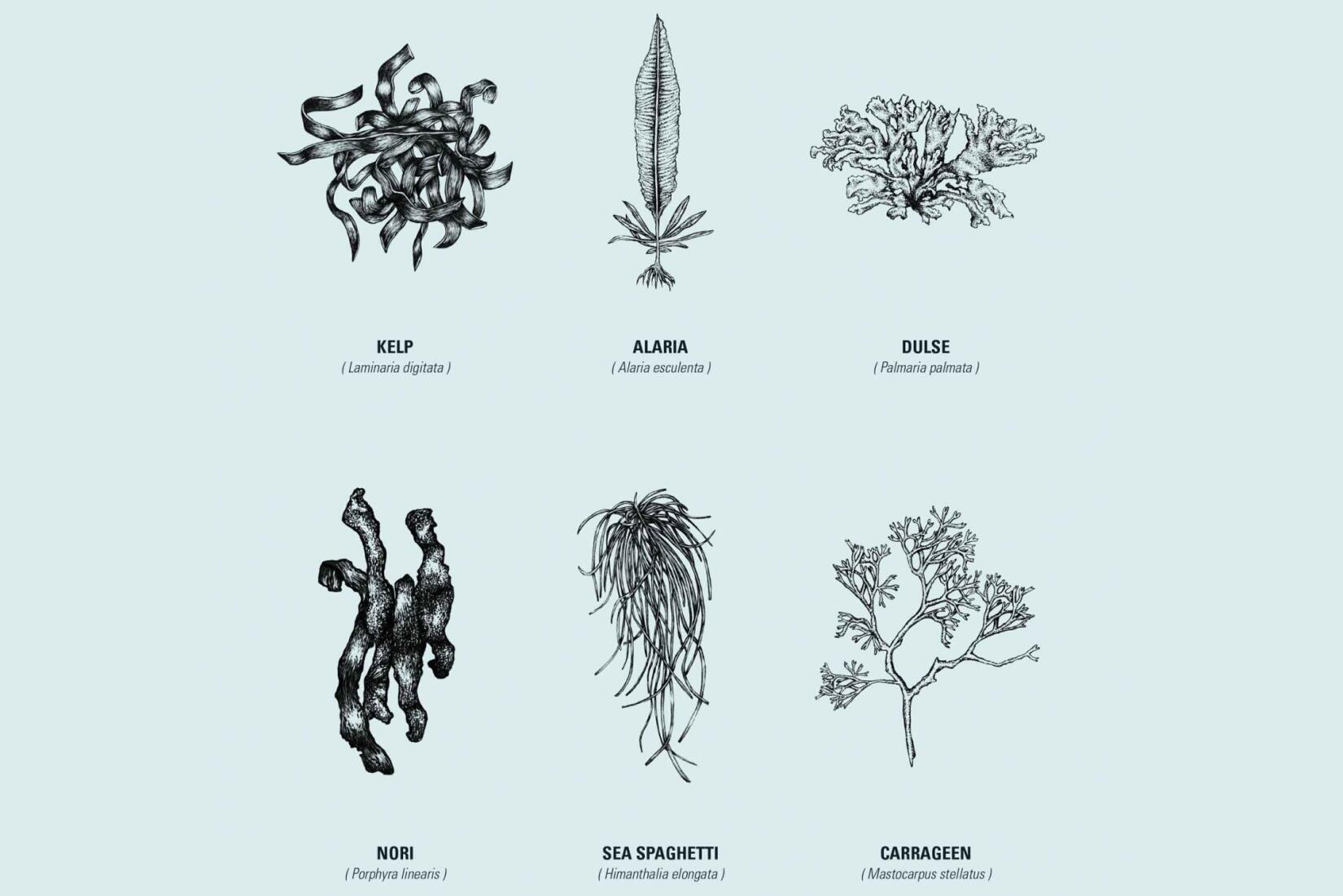

Kelp

Known as kombu or sea ribbon for its thin and intertwining fronds, kelp was once used to make potash for the glass industry. Today kelp is more readily found as the essence of dashi stock.

Alaria

Meaning ‘wings’ in Latin, alaria is also called Atlantic wakame or dabberlocks. In spring, alaria grows up to four meters long on the low shore. A powerful source of vitamins B and C, it imparts a soft, chicken flavour when cooked with rice.

Dulse

Dulse flat floating digits a deep red that are harvested sustainably from spring to autumn. Traditionally used as a substitute for chewing tobacco, its rich peppery flavour has recently been developed as an alternative to bacon.

Nori

Laver, as it is known in Wales, nori glistens like oil slicks on the rough surfaces of rocks. It has a mild nutty taste. Nori ‘fluffed’ from more exposed rock has sweeter notes.

Sea spaghetti

Sea spaghetti begins life as a ‘button’ and grows in dark green strands. Rich in calcium and magnesium it is usually served with pasta and lends a distinctly beefy flavour when added to soup.

Carrageen

Characterised by its spongy look on the mid to low shore, and for its anti-viral and adhesive properties, carrageen is used in the production of ice cream, toothpaste and lipstick. It was once a staple Irish desert — a cruel, lactic white pudding called Irish Moss that has thankfully fallen out of favour.