Finding your rhythm | Stories

Why does the shift from winter to spring affect our minds? What rhythms and routines should we follow and which should we challenge?

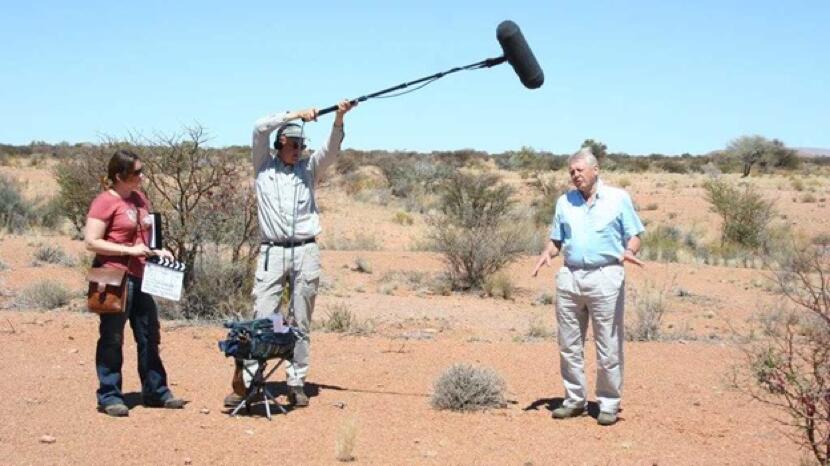

Read moreFrom the arctic ice of Norway to the humble rock pool, the sounds of the ocean are endlessly fascinating – if you have the right guide. We join Chris Watson, long-time Sir David Attenborough collaborator, on the hunt for one of his favourite sounds of all.

Earlier this year, Chris Watson used hydrophones to record the grazing sounds of limpets at Watergate Bay.

To find out more about Chris Watson and his career following the sounds of the sea, listen to ‘Oceans of Noise’, Chris Watson’s three-part journey into the ocean’s sonic environment, from marine life to seismic explosions.

From the arctic ice of Norway to the humble rock pool, the sounds of the ocean are endlessly fascinating – if you have the right guide. We join Chris Watson, long-time Sir David Attenborough collaborator, on the hunt for one of his favourite sounds of all…

Splish. Splosh.

Chris Watson is fishing for sound. He’s just dropped a pair of hydrophones (underwater microphones that respond to vibration), into the shallow water of a rock pool in a deserted northern corner of Watergate Bay. Now he dangles the cable like a baited line. “There's no magic technique in these circumstances,” he says, in his quietly enthusiastic Sheffield drawl. “You just throw it in and hope.”

As the long-time field recordist for Sir David Attenborough, Chris’s rich and varied recording career has taken him from the South Pole to the North. His trusty hydrophones have brought back some of the weirdest, most wonderful sounds in nature – whether the echolocation clicks of bottle-nosed dolphins or the guttural squelch of South Australia’s giant earth worm. “A few weeks ago I was recording cod off the coast of Norway,” he says, as if that was the most natural sentence in the world.

Here Chris is hoping to capture one of his favourites: the sound of limpets grazing. Beneath their conical shell, limpets feed with a radula, a tongue-like organ that’s equipped with more than 100 rows of teeth. So while they may appear the silent type, they actually make a rhythmic scraping sound as they harvest algae from the rock. “A chorus of those is wonderful,” says Chris.

One of the most striking examples of Chris’s ‘throw and hope’ hydrophone technique came in 2010, in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, when filming Attenborough’s Frozen Planet for the BBC. Having walked a couple of hundred metres out onto the Arctic ice, he screwed a hole beneath his feet and dropped his instruments into the mysterious depths below.

Then he put on his headphones.

The sound that came back was like a fathomless sub-aquatic concert hall.

“It was the most hauntingly beautiful thing,” he says. “The sound of male bearded seals hanging head-down, singing descending glissando tones in the darkness to gather their harem of females. They sounded like a choir, but some may have been 20 kilometres away. It was astonishing – like listening to the sounds of another planet.”

After even a short conversation with Chris, it soon becomes apparent just how much there is to be gained by tuning your ears beyond the immediate. And in actively listening. Even the rumble of surf starts to sound different – first more insistent, then more nuanced. “I’m sure sound is part of the embodiment and spirit of a place,” says Chris. “This beach has a signature sound like nowhere else.”

Chris began his audio career in the 1970s, as a member of Sheffield band Cabaret Voltaire, using the tape recorder as a creative instrument and performing with the likes of Joy Division. But while he works with sound in all its facets, he is particularly fond of the soundscape within our oceans. Water, he explains, is the most sound-rich medium on the planet, where vibrations travel almost five times faster than they do through air.

If you listen to that, you experience how shrimp hear the sound of the Atlantic coming through the sand.

Not that this rock pool appears, at first, to be the best example. Aside from a couple of large rocks bordering one end, it is otherwise almost featureless. Chris remains enthusiastic. “It's just endlessly fascinating, listening to nothing,” he says. “This appears to be a silent world, as Jacques Cousteau once described the ocean. It’s anything but.”

He passes the headphones. “If you listen to that, you experience how shrimp hear the sound of the Atlantic coming through the sand.”

At first, that sound is a rumbling white noise. But once you try putting yourself in a shrimp’s shoes, the whole picture shifts. With closer listening, other sounds emerge too: a squeaking seaweed; a sudden scuttling which, Chris suggests, is a hermit crab; the shrimps’ own high-pitched squeal made by rubbing its limbs together.

For Chris, the journey into sound began with a ‘silent movie’. As a child of 12, he was gripped by the action of the grey tits, blue tits and sparrows feeding beyond his kitchen window. For his birthday that year, his parents gave him a battery-powered reel-to-reel tape recorder. He was fascinated, and before he clocked its true potential he’d recorded everything from the vacuum cleaner to the toilet flushing.

Then one day he loaded it with ten minutes of tape, took it out to the bird table, and set it recording. When the tape ran out he hurried to recover it and play it back. He heard the sounds of those birds and was suddenly “transported to another world, another place where we could never be”.

It’s a place he’s been forever drawn to since.

Chris spots a second rock pool, to the east of the first. This one appears more interesting, full of enticing nooks, gullies and shadows. And there on the edge, glued stoically to the rock, sit two limpets. He puts the headphones on again.

Nature doesn't read a script

It’s now 25 years since Chris first donned his cans for Attenborough, in his groundbreaking Life of Birds series. The two instantly clicked. Again, sound played a critical role, as Chris found he wasn’t alone in his love and appreciation of its powers.

Attenborough was among the first to take a portable tape recorder on location for natural history films, way back in 1951, when the gear really wasn’t designed for the rigours of the field. “He was pushing it to its limit,” Chris says. “He was a real pioneer.”

And Chris was soon delighting the pioneer with innovations of his own. The BBC’s Life of the Undergrowth was conceived to capture the life-and-death drama of the world’s tiniest creatures and turn it into a full cinematic spectacular. Chris’s task was to do the same for their sounds. He began to explore the potential of personal lapel mics, the type used to record Attenborough’s monologues, experimenting with planting them on the edges of cobwebs and inside nests. If he spaced them correctly, it turned out, even tiny movements were massively amplified. The results were a revelation: the sound of Matabele ants, fresh from raiding a colony of termites, whistling a victory song on their return. “Hearing that and playing it to David – that was a remarkable moment,” says Chris.

Back at the rock pool, Chris is beaming again. He passes the headphones. They play the syncopated scratching of the two limpets, an intimate call-and-response chorus. “Absolutely crazy,” Chris says. “Fantastic. I love doing this because it’s so completely unpredictable. You might sit here till the tide comes in and not hear anything. Or in 15 minutes you might hear something amazing. I like that nature doesn’t read the script.”

He presses record and stands for a few minutes in silence. As his ears soak in the sound, his eyes rise up to watch the relentless crashing of the Atlantic.

“You might sit here till the tide comes in and not hear anything. Or in 15 minutes you might hear something amazing. I like that nature doesn’t read the script.”

He and Attenborough have a running debate: Chris likes to insist that the Atlantic surf sounds different to the Pacific – it’s sharper, he says, while the Pacific is softer, more gentle. Attenborough was apparently “incredulous that it might be the case”. So Chris recently made his friend a two-track CD, comprising a recording of each, to prove his point. Apparently he stubbornly refuses to concede that Chris is right.

Pleased with his limpet chorus, Chris gathers his line back in and packs up, carefully brushing the sand from the case containing his recorder. On the walk back he begins to enthuse about the intelligence of orcas, a sensitive species he’s recorded from the Antarctic to the Arctic, which uses echolocation sound in a way we’ve barely begun to comprehend.

But, mirroring a new sombre slant to the pair’s more recent documentaries, Chris’s tone here is laced with sadness. “There's so much interesting work being done in the oceans,” he says. “But we’re messing it up with so much noise pollution, before we understand what things are being said there.”

He explains how hydrophones on the East Coast of America have monitored humpback whales coming up the Cornish coast, and can hear them calling back to their peers in the East Atlantic. But those same hydrophones can also hear ships passing Ireland – 2,500 miles away.

Such reflections are now an unwelcome fixture of his travels with Attenborough. These days the two tend towards long discussions with the stresses placed on nature in the time they’ve been travelling together, whether that’s specific glaciers in Iceland receding, or the sea ice melting around the North Pole. “It's chilling,” says Chris. “It’s sickening to see it, and quite scary. I worry. It’s happening – in some places literally – in front of our eyes.”

Chris is proud that Attenborough has become such a figurehead in the drive to protect our climate. But his work with sound surely has a vital role to play too: the more we turn our senses beyond the obvious, to pay attention to the untold wonders that comprise our natural world – and to feel the vast benefits that can bring us – the more likely we are to be inspired to fight for them.

The pair are about to embark on further adventures, across Croatia, Costa Rica and California, as they record an update of the series Life of Plants. For now, though, he’s here at Watergate Bay, watching the sky paint itself in pastels, as he sets up a microphone to record the ocean with the evening tide coming in.

As Chris is keen to point out, even the Atlantic’s relentless, razor-sharp roar is the expression of something far more delicate and wonderful: it’s the sound of hundreds of millions of bubbles, bursting.

Listen Up

Even if you don’t own a hydrophone, there are plenty of soundscapes to explore in the Bay.

Falling thunder.

The sight of swell stacked to the horizon is always welcome on Cornwall’s coast, but it’s worth spending a moment listening in, before waxing up your board. Concentrate on the rhythm of the sound, training your ear in on each wave as it lands to hear the layer upon layer of noise coming together.

Snap, crackle, pop.

Barnacles are noisy beasts. Covering the rocks that are exposed on Watergate Bay at low tide, their fizzing as tiny air bubbles pop and sometimes tapping as they move in their shells makes a symphony of shoreline sound. Head down to the rock cluster as the tide drops and listen as the water washes over them.

Sundown stridulation.

Climb the coast path along the Bay as the sun starts to set and listen out as the air fills with the vibrations of insects calling. Rubbing their limbs together to communicate, it’s a sound that shouts out summer.

We'd love to keep in touch and send you the latest news, events, competitions and offers from the Bay. Sign up to receive our e-newsletter.